Snails use their shells as a weapon against parasitic worms

Parasitic roundworms that invade a snail’s shell may be trapped, encased and fixed permanently to the inner layer of that shell, as Robbie Rae shows.

Thanks to its shell, a snail is protected against damage, predators, heat and cold, drought and rain. But there is more, as Robbie Rae discovered. The snail also uses its shell as a defence system to eliminate parasitic roundworms (nematodes). These parasites attack snails since snails appeared on earth, about 400 million years ago. It is obvious that snails had to evolve a defence mechanism against these enemies, but until now, no defence mechanism was known.

Encapsulation

In his lab, Rae exposed grove snails (Cepaea nemoralis) to the nematode Phasmarhabditis hermaphrodita for several weeks. This bottom dwelling animal, less than 2 millimetres long, is able to penetrate and kill many snail and slug species, but some snails are resistant, as for instance the grove snail. Rae studied the interaction between the grove snail and the worms to find out how the snail eliminates the parasites.

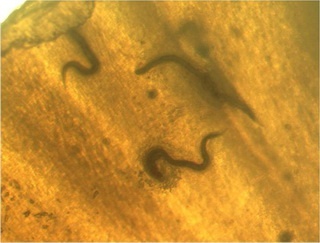

It turned out that the cells on the inner layer of the shell do the job. They adhere to an invading worm, multiply, and swarm over the parasite’s body until it is entirely covered. Engulfed by the cells, it is fused to the inside of the shell and dies. By this procedure, grove snails not only encapsulate this lethal roundworm, but they use the immune reaction also to kill other, less dangerous nematodes, as experiments showed.

It turned out that the cells on the inner layer of the shell do the job. They adhere to an invading worm, multiply, and swarm over the parasite’s body until it is entirely covered. Engulfed by the cells, it is fused to the inside of the shell and dies. By this procedure, grove snails not only encapsulate this lethal roundworm, but they use the immune reaction also to kill other, less dangerous nematodes, as experiments showed.

In nature, this is common practice. Rae collected grove snails and white-lipped snails (Cepaea hortenis) from the wild and observed that many snails had different species of roundworms attached to their inner shell surface, up to 100 worms in one shell. Also the garden snail (Cornu aspersum) – like the other two snail species an inhabitant of Western Europe – uses its shell to eliminate invading worms by encapsulation.

Old defence

Finally, he examined a large number of snails from museum collections, to conclude that many snails of many different species had nematodes attached to their shells. Trapped worms proved to be fixed permanently; they even can be found in snails that died a few hundred years before. As this defence mechanism is found to be widespread among the large and old clade of terrestrial snails and slugs, it must have evolved about 100 million years ago. Even some slug species eliminate parasitic roundworms by this mechanism. During evolutionary history, their shells have become reduced and internalised, but in many species they retained the ability to trap, encase and kill roundworms.

The vineyard snail (Cernuella virgata) is one of the species that is unable to get rid of the roundworm Phasmarhabditis hermaphrodita. Apparently, the parasite evades its immune reaction in one way or the other. As many slug species are also susceptible to this parasite, it is formulated into a biological control agent to be used against herbivirous slugs.

Willy van Strien

Photos:

Large: grove snail, Cepaea nemoralis. Kristian Peters (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

Small: nematodes fixed to the inner layer of a grove snail’s shell. © Robbie Rae

Source:

Rae, R., 2017. The gastropod shell has been co-opted to kill parasitic nematodes. Scientific Reports 7: 4745. Doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-04695-5