Squid male changes its mating tactic when growing larger

When becoming sexually active, male squids are little successful at first. Only later they perform better, increasing their chances to sire offspring. This development includes major changes, Lígia Apostólico and José Marian discovered.

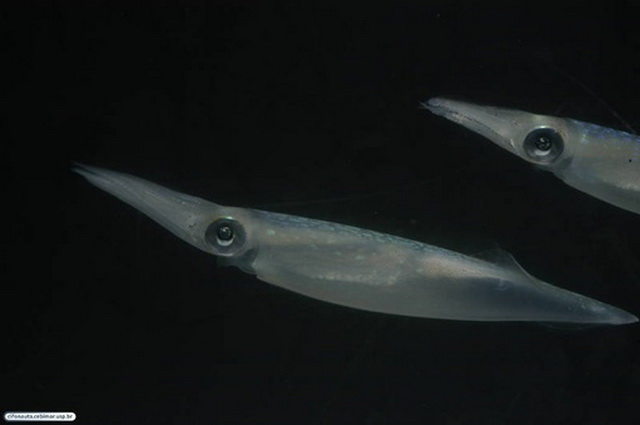

In squid like Doryteuthis pleii, a species living off the coast of Brazil, small males are able to mate, but they have to do it at an inappropriate time and in a little successful way, as sneakers. Large males act much more effectively as real partners or consorts, as Lígia Apostólico and José Marian report.

Shooting mechanism

When squid mate, s male delivers sperm packages to a female. With a special arm, a male takes the packages, spermatophores, from the spermatophoric sac, where they are produced, and places them on the body of a female with a rapid movement. Then he is done, the sperm packages themselves will do the rest of the work. With a shooting mechanism (ejaculatory apparatus), a package turns inside out, and when evaginated, it attaches onto the female’s body and the sperm cells swim out.

A large male delivers its sperm packages neatly. He approaches a female that is about to release her eggs, places himself next to her with his head pointing in the same direction as hers, moves his special arm behind her head under the mantle that surrounds her body and places his spermatophores near the opening of the oviduct from which the eggs will be released in capsules. The sperm cells have immediate access to the eggs. The male guards the female and tries to keep rivals at bay with flickering colour patterns, because if another male also mates with her, his sperm will have to compete with that other male’s sperm.

Aggregate

A small man does not stand a chance against a large one, so he can only mate at a less exciting time, when no eggs are to be released soon. He doesn’t put his arm under the female’s mantle, but he assumes a head-to-head position and places his sperm packages under her beak, that is between the arms. When she releases the eggs, she holds the capsules for a while near the beak before depositing them on the substrate, and then a sneaker’s sperm cells have a chance – as far as the eggs are not fertilized already by a consort’s sperm.

The sperm cells of sneakers are adapted to the unfortunate site where they are placed and the wide time interval between mating and fertilization chances, and their spermatophores differ from those of consorts. Sneakers have smaller and thinner spermatophores; after evagination, they are short and club-like shaped. The sperm cells come out slowly and aggregate at the exit, having nothing to do there for the time being. The spermatophores of consorts, in contrast, are larger and after evagination, they are long and hook-like shaped. The sperm is quickly discharged in a powerful flow and sperm cells immediately diffuse, so the eggs that are released will pass through a cloud of them.

Now in Doryteuthis pleii, Apostólico and Marian found some males, intermediate in size between sneaker and consort (about 17 centimetres mantle length), that produce sneaker-like spermatophores as well as consort-like spermatophores, and often also an intermediate form. The sneaker-like packages are oldest and stay in the anterior part of the spermatophoric sac, the consort packages are youngest and reside in the posterior part, and the intermediate packages are to be found in between.

Fast switch

This indicates that a male starts as a sneaker and, if he exceeds a certain size limit, he will go on as a consort, implementing all changes that are required by the transition. Age estimates show that sneakers are indeed younger than consorts; the estimates are based on the size of small particles in the organs that enable the animals to control their position and balance; every day these particles, statoliths, increase a little in size. The switch from sneaker to consort must take place very fast, as only few males are found that are in transition.

So, during their lives, which lasts less than a year, the males go through a major development. They are small when at summer the mating season starts, but still they mature sexually, so that they can begin to reproduce – although for the time being only as little successful sneakers.

But perhaps not all males follow that path, Apostólico and Marian think. Males that were born early, in late summer or autumn, have much time before the mating season starts. They can grow to a large size before they become sexually active, and then they can be consorts from the start.

Willy van Strien

Photo: Alvaro E. Migotto (Cifonauta. Creative Commons CC BY-NC SA 3.0)

Sources:

Apostólico, L.H. & J.E.A.R. Marian, 2018. From sneaky to bully: reappraisal of male squid dimorphism indicates ontogenetic mating tactics and striking ejaculate transition. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 123: 603-614. Doi: 10.1093/biolinnean/bly006

Apostólico, L.H. & J.E.A.R. Marian, 2018. Dimorphic male squid show differential gonadal and ejaculate expenditure. Hydrobiologia 808: 5-22. Doi: 10.1007/s1075

Apostólico, L.H. & J.E.A.R. Marian, 2017. Dimorphic ejaculates and sperm release strategies associated with alternative mating behaviors in the squid. Journal of Morphology. 278: 1490-1505. Doi: 10.1002/jmor.20726