Ant swallows its own formic acid to stay healthy

Formic acid appears to be a great help for ants to prevent infection from contaminated food, Simon Tragust and colleagues discovered. A gulp after each consumption increases their survival chance.

People like sweet desserts, but for ants of the subfamily Formicinae it is different. They take a gulp of formic acid after eating or drinking, Simon Tragust and colleagues witnessed.

This is remarkable, because formic acid is an aggressive substance. Formicinae ants produce it in a venom gland that has an opening at the tip of the abdomen. They were known to spray it at predators, such as birds, spiders, and insects, to defend themselves, and this is understandable. But swallowing?

Disinfect

Tragust and colleagues had shown previously that Formicinae ants use their acid not only against predators, but also against pathogens. Workers apply it in combination with resin to keep an entomopathogenic fungus (Metarhizium brunneum) out of their nest.

Also, they use formic acid to keep the brood clean. If they detect pupae covered with spores of the pathogenic fungus, they clean them and cover them with formic acid, which they had taken up from the abdominal gland opening into the mouth.

If fungal spores have already germinated on a pupa and the fungus has penetrated the cuticle, workers unpack the infected pupa from its cocoon, bite holes in the skin and inject formic acid. In this way, they prevent the fungus from growing and forming spores that will contaminate the rest of the colony. The pupa does not survive the treatment, but it would have been killed by the fungus anyway.

Crop acidity

Now, a new application of formic acid comes to light: Formicinae ants swallow their own formic acid after eating or drinking something. Tragust deduces this from tests in the lab with Florida carpenter ant, Camponotus floridanus. He offered ants honey water or plain water and saw them lick their abdominal tip afterwards. Apparently, they then took up acid into the mouth and swallowed it, as Tragust showed that the contents of their crop, just before the stomach, became very acidic.

Perhaps, the idea was, workers take formic acid to kill bacteria that may be present on food. And that was the case, as became clear from tests in which workers were given food that was contaminated with a pathogenic bacterium species (Serratia marcescens). In ants that then took a gulp of formic acid, bacteria did not survive the crop environment and the rest of the intestinal system remained clean. Ants that were prevented from taking in acid, were at greater risk of a deadly infection.

Only bacteria that thrive in acidic environments survive the acidic crop, and such bacteria populate the ants’ intestines. But these are beneficial bacteria that help digest food. The acid appears to be an excellent remedy against pathogenic microbes.

Fortunately, we don’t have to take an extremely sour dessert like Formicinae ants, because our stomach keeps itself acidic.

Willy van Strien

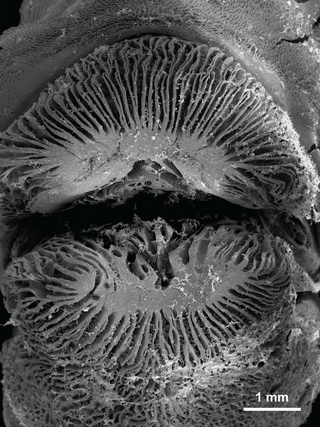

Photo: Carpenter ant, Camponotus cf. nicobarensis. ©Simon Tragust

Ants also use formic acid to keep fungus out of nest

Sources:

Tragust, S., C. Herrmann, J. Häfner, R. Braasch, C. Tilgen, M. Hoock, M.A. Milidakis, R. Gross & H. Feldhaar, 2020. Formicine ants swallow their highly acidic poison for gut microbial selection and control. eLife 9: e60287. Doi: 10.7554/eLife.60287

Pull, C.D., L.V. Ugelvig, F. Wiesenhofer, A.V. Grasse, S. Tragust, T. Schmitt, M.J.F. Brown & S. Cremer, 2018. Destructive disinfection of infected brood prevents systemic disease spread in ant colonies. eLife 7: e32073. Doi: 10.7554/eLife.32073

Tragust, S., B. Mitteregger, V. Barone, M. Konrad, L.V. Ugelvig & S. Cremer, 2013. Ants disinfect fungus-exposed brood by oral uptake and spread of their poison. Current Biology 23: 76-82. Doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.11.034