Venus flytrap controls the trapping process in several ways

Carnivorous plants should control their energy budget, otherwise the benefits of capturing insects will not compensate for the costs. The Venus flytrap has several mechanisms to limit waste of energy, Andrej Pavlovič and colleagues discovered.

To us, it is almost impossible to catch a fly. But the Venus flytrap has no difficulty. The plant (Dionaea muscipula) occurs in North and South Carolina (United States), where it grows in sunny, wet areas on poor soil; it can grow there by ‘eating’ insects. The catch of a fly yields lots of nutrients, but the process also demands lots of energy, and the balance between yield and costs must be positive, otherwise the plant will not grow. So, it has evolved a number of control mechanisms to minimize waste of energy, as Andrej Pavlovič and colleagues point out.

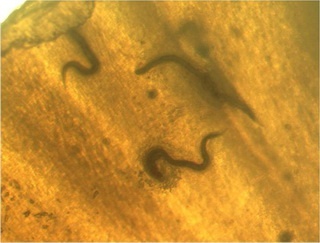

The leaves are arranged in a rosette, and each leaf has a double-lobed trap at the top with a row of ten to twenty teeth at the edge of each lobe. Glands along the edges secrete a sugary substance that attracts insects. Each lobe has a few trigger hairs that respond when touched by an insect, causing the trap to snap shut rapidly. The central zone of the trap contains glands secreting enzymes that digest a trapped prey and proteins that enable the glands to absorb the nutrients that are released upon digestion.

The leaves are arranged in a rosette, and each leaf has a double-lobed trap at the top with a row of ten to twenty teeth at the edge of each lobe. Glands along the edges secrete a sugary substance that attracts insects. Each lobe has a few trigger hairs that respond when touched by an insect, causing the trap to snap shut rapidly. The central zone of the trap contains glands secreting enzymes that digest a trapped prey and proteins that enable the glands to absorb the nutrients that are released upon digestion.

The Venus flytrap has to invest a lot of energy to keep the traps operational and to produce lures, digestive enzymes and absorption proteins. How does the plant control these costs?

1: Two times

First of all, a trap will not snap shut until trigger hairs are touched at least twice within twenty seconds, when there is a fair chance that an insect has landed. So, a trap will not close when a for instance a wind-blown dust grain touches a trigger hair.

2: Panic

But not every animal that landed turns out to be a nice fat fly. Upon closure, small gaps between the marginal teeth allow little insects that are not worth the effort to digest them to escape. If the trap is empty, it will reopen again after a few hours. But if a large insect is encased, it will struggle in panic, and his movements induce the trap to seal hermetically. After the trigger hairs have been touched at least five times, the secretion of digestive enzymes and absorption proteins starts, and the more movements the prey makes, the more enzymes and proteins will be secreted.

3: Limited reaction

Still, a trap may snap shut, close tightly and secrete digestive enzymes and absorption proteins in vein. This happens when it is damaged. The cause of the error is to be found in the evolution of carnivorous plants, for the habit to capture insects probably evolved from defence mechanisms against herbivorous insects. In ordinary plants, herbivory generates an electrical signal, which in turn stimulates the accumulation of plant hormones, jasmonates. These will induce the plants to synthesize toxins that harm the insects, not only locally on the place of damage, but also elsewhere in the plant, as a precaution. In carnivorous plants, such as the Venus flytrap, things have a bit changed. In these plants, the presence of an insect triggers an electrical signal that induces the accumulation of jasmonates; these hormones stimulate the secretion of digestive enzymes and absorption proteins. The electrical signal also induces the trap to close.

Now, Pavlovič conducted an experiment in which he repeatedly wounded a trap of Venus flytraps by piercing it with a needle to mimic herbivory, and noticed that the trap showed the same response as when the trigger hairs wouldhave been touched by an insect: the trap closed and jasmonates accumulated; if he continued damaging every few minutes, the traps secreted digestive enzymes and absorption proteins – to no end. But the misplaced reaction was limited to the local trap that was damaged and did not occur elsewhere in the plant, in contrast to defence reactions agains herbivores.

4: Process stops

The secretion of digestive enzymes and absorption proteins does not run at full speed from the start. Only when certain substances from an enclosed prey are released, the rate of secretion increases to the highest speed. If there is no prey, the process will stop. So, the plant doesn’t waste much energy when it is misled.

After about ten days the fly is digested and the fall will reopen again.

Willy van Strien

Photos

Large: ©Andrej Pavlovič

Small: Olivier License (via Flickr, Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Sources:

Pavlovič, A., J. Jakšová & O. Novák, 2017. Triggering a false alarm: wounding mimics prey capture in the carnivorous Venus flytrap (Dionaea muscipula). New Phytologist 216: 927-938. Doi: 10.1111/nph.14747

Böhm, J., S. Scherzer, E. Krol, I. Kreuzer, K. von Meyer, C. Lorey, T.D. Mueller, L. Shabala, I. Monte, R. Solano, K.A.S. Al-Rasheid, H. Rennenberg, S. Shabala, E. Neher & R. Hedrich, 2016. The Venus flytrap Dionaea muscipula counts prey-induced action potentials to induce sodium uptake. Current Biology 26: 286-295. Doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.11.057

Libiaková, M., K. Floková, O. Novák, L. Slováková & A. Pavlovič, 2014. Abundance of cysteine endopeptidase dionain in digestive fluid of Venus flytrap (Dionaea muscipula Ellis) is regulated by different stimuli from prey through jasmonates. PLoS ONE 9: e104424. Doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0104424

Pavlovič, A., V. Demko & J. Hudák, 2010. Trap closure and prey retention in Venus flytrap (Dionaea muscipula) temporarily reduces photosynthesis and stimulates respiration. Annals of Botany 105: 37-44. Doi:10.1093/aob/mcp269