The immune system of deep-sea anglerfishes is strongly modified

To the well-known peculiarities of deep-sea anglerfish, Jeremy Swann and colleagues add a new one: some species lack an important part of the immune system. This is associated with a unique parasitic lifestyle of males.

There are strange, very strange and extremely weird animals. We can safely include deep-sea anglerfish in the latter group.

Within the anglerfish (Lophiiformes), they form a separate group of over 160 species, the Ceratioidea, which, as the name indicates, have specialized in living in the utter darkness of the deep sea. Food and partners are extremely scarce down there. Hence, as was known, these fish exhibit some peculiarities. Now, it turns out that they also have a very aberrant immune system, Jeremy Swann and colleagues report.

Angling pole with glowing bulb

Deep sea anglerfish start their lives in a quite normal way, eggs and larvae dwelling in surface waters. But once they developed into young fish, things change. Females grow to a considerable size, males stay tiny.

The bigger a female gets, the more eggs she can produce. And so a young female starts growing. She has to eat much, several prey animals are on her menu. To capture prey, she uses a fishing rod growing from her back; it is a modified anterior dorsal fin. At the end it has a lure: a bulb in which bacteria live that produce light by carrying out a chemical reaction. It is a form of mutualism; the bacteria get a place to live in and food in exchange for light production.

An anglerfish’s light can flash and dance, resembling a moving animal. Living animals discern a tasty snack which they will approach. The anglerfish then ingests a large amount of water, including prey. With some luck, the catch will provide sufficient nutrients to sustain her for quite a while.

The females, plump and with large heads and mouths full of sharp teeth, are not the prettiest of all. They are bad swimmers, drifting around, just waiting for prey to come by.

Strong attachment

After completing the larval stage, males’ development takes a completely different direction. Males no longer grow and are unable to eat. Their only goal is to find a female in the empty deep sea. So, they swim constantly. In addition to the light bulb of their angling rod, young females also have two luminous organs on their backs. Maybe the dwarfed males, which have big eyes, are able to detect those organs. If they are lucky, they will meet a partner before they have used up all their reserves.

Upon meeting, he attaches himself to her body with sharp teeth. When, later on, she is ready to release eggs, he is ready to fertilize them. Males and females only become sexually mature when they’ve acquired a partner. Given the scarcity of conspecifics, this makes sense: only after pair formation it is guaranteed that eggs and sperm can come into contact.

Sperm bulge

In some deep-sea anglerfish, the attachment between female and male is temporary; after a while, he lets go.

But in other species, males attach themselves permanently to a female. These are most bizarre types, because the two partners fuse with each other, enabling the male to survive. Their skin tissues meld, the circulatory systems become connected. He now is a ‘sexual parasite’, little more than a sperm-producing bulge that feeds on nutrients that he derives from her. This sexual parasitism is a unique mode of reproduction, occurring only in deep-sea anglerfish.

It is called parasitism, but it may be considered a form of mutualism as well, as the male delivers sperm in return for nutrients.

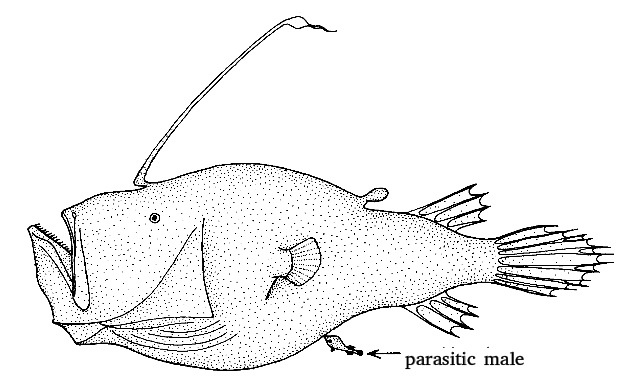

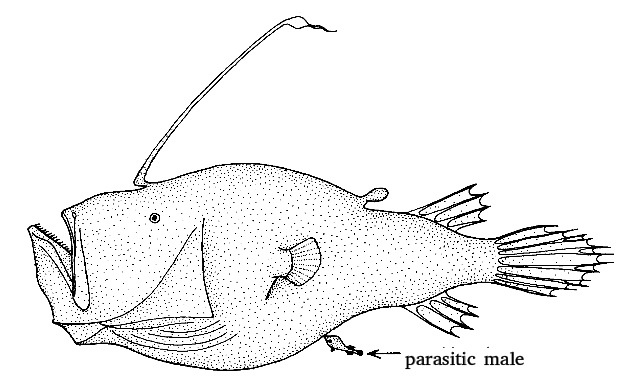

The best known species is Ceratias holboelli; it is also the largest one and it has the most extreme sexual dimorphism. A female can grow more than a meter long (including tail), sixty times the size of a free-living male. Physical pair formation is permanent. Once attached to her belly, he grows to a maximum of 20 centimetres. A female carries no more than one parasitic male.

Another species with permanent attachment is Cryptopsaras couesii; in this species, up to eight males can be attached to a single female. A female can be 30 centimetres long, a free-living male only three centimetres.

Ancient immune system

It is remarkable that the female immune system doesn’t attack permanently attached, parasitic males, Swann and colleagues realized. You would expect the immune system to recognize and reject such males, as they are not-own tissue. But that does not happen.

Apparently, the immune system tolerates the very intimate mode of reproduction. To find out how, the biologists examined a number of genes that underpin various parts of immune defence. They investigated four deep-sea anglerfish species with temporarily attached males and six species with permanently attached parasitic males, including Cryptopsaras couesii. They compared these species to a number of anglerfish species outside the deep-sea group, where males don’t attach to females.

Fishes have the same immune system as other vertebrates; the system is 500 million years old. It consists of innate, general immune responses on the one hand and specific immune responses that build up against specific intruders that the system has to deal with on the other hand. The researchers focused on the adaptive, specific immune system.

Lethal

The results were surprising: deep sea anglerfish species in which males live as parasites on females lack essential immune genes. Their specific immune system is severely blunted.

In two of the species studied, species in which females can have more than one male attached, virtually no specific immune facilities are functional. This is highly remarkable, because such complete lack of specific immune defence is lethal for other animals. The first infection would kill them. Microbial pathogens occur in the deep sea too, so deep-sea anglerfish must be able to defend themselves. Most likely, they reorganized their innate immune defence, the researchers assume.

From their own and other research, they conclude that the common ancestor of deep-sea anglerfish had tiny, non-parasitic males that temporarily attached themselves to females. On a few occasions, species descending from that ancestor made the switch to permanent attachment and their specific immune defence has been largely dismantled.

It is unclear yet what happened first. Did males become parasitic, making it necessary to turn off the specific immune system? Or did the specific immune system lose important parts, making permanent attachment of males possible?

The deep sea anglerfish remain really puzzling creatures.

Willy van Strien

Drawing: northern giant seadevil, Cryptopsaras couesii (not included in this research); female with male attached. Tony Ayling (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons CC BY-SA 1.0)

Watch the fanfin angler, Caulophryne jordani (not included in the research) on YouTube; female with permanently attached male

Sources:

Swann, J.B., S.J. Holland, M. Petersen, T.W. Pietsch, T. Boehm, 2020. The immunogenetics of sexual parasitism. Science, online July 30. Doi: 10.1126/science.aaz9445

Fairbairn, D.J., 2013. Odd couples. Extraordinary differences between the sexes in the animal kingdom. Princeton University Press, Princeton and Oxford, VS. ISBN 978-0-691-14196-1